| By Gale Staff |

Saint Patrick’s Day often slips by in classrooms without much thought—maybe a splash of green on a bulletin board or a quick mention of Ireland. But dig a bit deeper, and the holiday is brimming with untapped potential for a fun, standards-aligned lesson.

Educators with access to Gale In Context: Elementary can leverage young learners’ fascination with the green-clad clichés, immersing their imaginations in historical and fictional texts, videos, news articles, and pictures available through the Saint Patrick’s Day topic page.

As students work with leveled content and vivid visuals, they will naturally strengthen their reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills in the K–5 Common Core State Standards while also engaging with themes outlined by the National Council for Social Studies.

In other words, the St. Patrick’s Day portal piques students’ interest with age-appropriate content about this March 17 celebration and ensures that your seasonal lessons support your district’s broader academic goals.

Not sure if Gale In Context Elementary is right for your classroom? You’re in luck! We’ve rounded up a selection of supplementary materials about the holiday’s origins, symbols, and traditions to spark elementary students’ curiosity on Saint Patrick’s Day.

Separating Fact from Folklore with the Legend of Saint Patrick

The holiday’s namesake, Saint Patrick (c. 385–461), wasn’t actually from Ireland at all. He was born in Roman Britain but was kidnapped as a teenager and lived in the province of Ulster, Ireland, as an enslaved shepherd until he escaped captivity years later.

Upon reuniting with his family, he began training as a Christian missionary and returned to Ireland to spread the religion to the island’s people.

Despite these well-documented elements of his life, much of what students might think they know about Saint Patrick arises from centuries of storytelling.

For instance, the tale of Saint Patrick driving the snakes out of Ireland is entirely legendary. The island had no snakes to begin with because its geographic isolation following the last Ice Age prevented these reptiles from ever inhabiting the land. Instead, the snakes in the tale are widely understood as symbols of pagan beliefs that were displaced as Christianity gained prominence.

Discussion Idea

After sharing a brief history of Saint Patrick’s life, ask students what they find most interesting about him. Then, have them brainstorm connections between Saint Patrick’s Day traditions—such as the color green and shamrocks—and the life and story of the saint behind the holiday.

Symbols of the Celebration

Thanks to the holiday’s popularity, the symbols of Saint Patrick’s Day have become instantly recognizable. This familiarity can be a starting point for elementary educators to teach the stories behind them, from their cultural roots to their modern-day meanings.

Shamrocks

According to legend, Saint Patrick used the three-leafed clover, or shamrock, as a teaching tool to explain the Christian concept of the Holy Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Each leaf represented one part of the Trinity alongside two other equal portions of the plant, in perfect symmetry—an apt depiction of unity, despite being distinctive entities.

However, historians have found no direct evidence that Patrick used the shamrock in his teachings. Instead, it was folklore cemented in history by a botanist and priest named Caleb Threlkeld when he wrote an entry on the shamrock in “Synopsis stirpium Hibernicarum alphabeticæ dispositarum,” a treatise on the native plants of Ireland.

In the 18th century, the shamrock took on new significance as a symbol of Irish nationalism worn to express solidarity in the face of British colonialism and has endured as an important representation of Irish pride.

The Color Green

Initially, blue—not green—was associated with Saint Patrick. When King George III established a chivalric order called the Anglo-Irish Order of St. Patrick, they chose a robin’s egg shade of blue, later called “Saint Patrick’s blue,” as its official color.

It wasn’t until the Irish Rebellion of 1798 that the color green came to be closely tied to Irish identity, as soldiers wore green uniforms to differentiate themselves from British forces.

Leprechauns

Leprechauns are among the most iconic figures in Irish mythology. They are part of a larger tradition of the Aos Sí, or supernatural beings, tied to Ireland’s ancient folklore. These stories depict leprechauns as solitary, industrious cobblers and mischievous tricksters who use their cunning and cleverness to outwit humans.

Over time, as Irish culture became more globally visible, leprechauns became increasingly linked to Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations—particularly outside of Ireland—due to commercialization and, in some cases, stereotyping.

Tracing the Origins and Evolution of Saint Patrick’s Day

The Catholic Church declared Saint Patrick’s Day an official feast day in 1631 in recognition of Patrick as the patron saint of Ireland. Because it coincided with Lent, it offered a rare chance to enjoy a feast amidst the season’s austerity.

The earliest Saint Patrick’s Day parade with substantial documentation occurred in 1762 when Irish soldiers serving in the British army marched through New York City. The event was adopted in subsequent years on a smaller scale by other militia and Catholic organizations, particularly in cities with growing Irish populations, such as Boston and Philadelphia.

With the arrival of large numbers of Irish immigrants in the mid-19th century, Saint Patrick’s Day events began to grow despite the hostilities that the Irish population faced at the time. Historian James Barrett explains:

“In places like New York and Chicago, Irish Americans were determined to make a place for themselves. The parades . . . were a way of saying, ‘We’re here, we’re proud of our culture, and we’re not going anywhere.’ [It was a] way of showing the broader urban community that the Irish had arrived.”

Interestingly, the tradition of Saint Patrick’s Day parades spread globally before taking root in Ireland. It wasn’t until 1903 that Ireland held its first parade. While serving in the House of Commons, James O’Mara introduced the Bank Holiday (Ireland) Act 1903, which declared March 17 a public holiday.

Dublin now sees more than 500,000 people gather each year for five days of festivities, including the Céilí Mór, an outdoor party featuring traditional Irish dancing.

Festivities Beyond the Éire Shores

Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated far beyond Ireland, or Éire in Irish Gaelic, and each iteration seems to take on a life of its own. Exploring these examples of regional traditions is an exciting way to introduce students to cultural diffusion and adaptation.

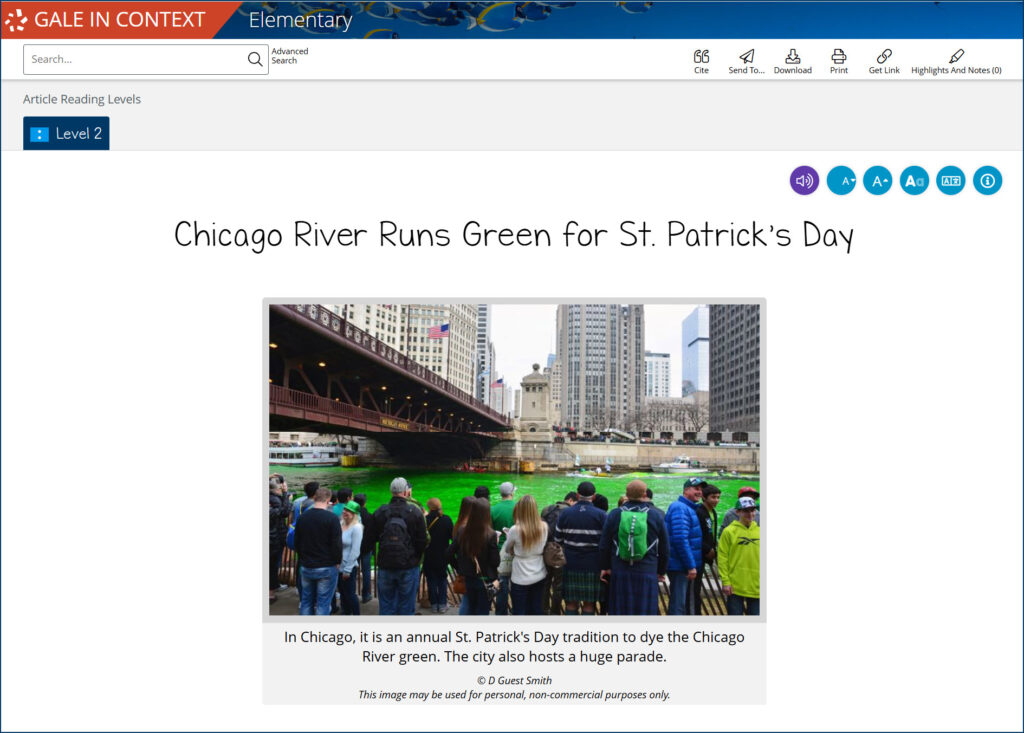

Chicago, United States

Few cities commemorate Saint Patrick’s Day as enthusiastically as the Windy City, where the celebration begins with the dyeing of the Chicago River. It all started in 1962 when a local plumbers’ union, experimenting with a dye to detect leaks, accidentally turned the water green. The plumbers’ union oversees the event and keeps the environmentally friendly formula a secret.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires has one of the largest Irish populations outside of Ireland, resulting in the Argentinian capital hosting the largest St. Patrick’s Day celebration in Latin America. In fact, its attendance numbers run neck-and-neck with Dublin’s!

In addition to “elves, fairies, bagpipers, and Irish dancers [honoring] the homeland with a parade,” the Retiro neighborhood puts on an all-out block party. Vendors set up stalls proffering traditional Irish fare and handicrafts.

Montserrat Island, West Indies

With a nickname like “The Emerald Island of the Caribbean,” it makes sense that Saint Patrick’s Day has become a public holiday on the island of Montserrat. The holiday’s presence on the island results from a complex and humbling history, tracing back to the 17th and 18th centuries.

During British colonization, Irish immigrants, fleeing repression at home, settled in Montserrat. They brought along their cultural traditions, including St. Patrick’s Day. While some of the Irish arrived as indentured servants, some of those oppressed became the oppressors, purchasing plantations that relied on slave labor. It was on Saint Patrick’s Day in 1768 when enslaved persons, expecting Irish plantation owners to be distracted by the festivities, organized a rebellion.

Today, the week-long event merges Irish and African traditions, with their parades including steel drum bands and masquerade dancers in elaborate, feathered costumes. One of the highlights is the Heritage Feast, a reenactment of the 1768 uprising.

Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo’s Saint Patrick’s Day event attracts thousands to Omotesando Avenue for Asia’s largest Irish festival. Japanese taiko drummers join Irish step dancers and costumed performers, creating entertainment for attendees perusing the countless food stalls lining the route, offering Irish staples like fish and chips alongside Japanese festival treats. Despite Tokyo having a community of less than 2,000 Irish people, the event is wildly popular.

Discussion Idea

Ask students to pick one country’s Saint Patrick’s Day traditions and identify which parts connect back to Irish culture—music, dancing, the color green, feasting—and which aspects were adapted from local culture. Encourage them to consider why these changes might happen, prompting discussion about how immigration, geography, history, and community values influence how celebrations evolve across time and place.

Gale In Context: Elementary Is a Passport to Holiday Histories from Around the World

With Gale In Context: Elementary, you can kindle young learner’s natural curiosity about holidays while still maintaining academic rigor, thanks to our collection of age-appropriate, reliable, curriculum-related content. Dedicated holiday portals help young learners discover the roots of traditions worldwide, from diya lighting during Diwali to gifting red envelopes for the Lunar New Year.

Contact your local Gale sales representative to introduce your young learners to a world of cultural celebrations or to request a free trial in time for Saint Patrick’s Day.